The Wolfson Library at the RAD

The Wolfson Library houses one of the largest specialist dance collections in the UK. We welcome researchers, educators and practitioners from around the world as well as RAD members, students and staff.

The collections on open shelves include books, journals, CDs, DVDs, conference proceedings, exhibition and auction catalogues and Benesh Movement Notation Scores. The Dance Collection is supplemented by the General Collection of resources on pedagogy, music, anatomy and physiology.

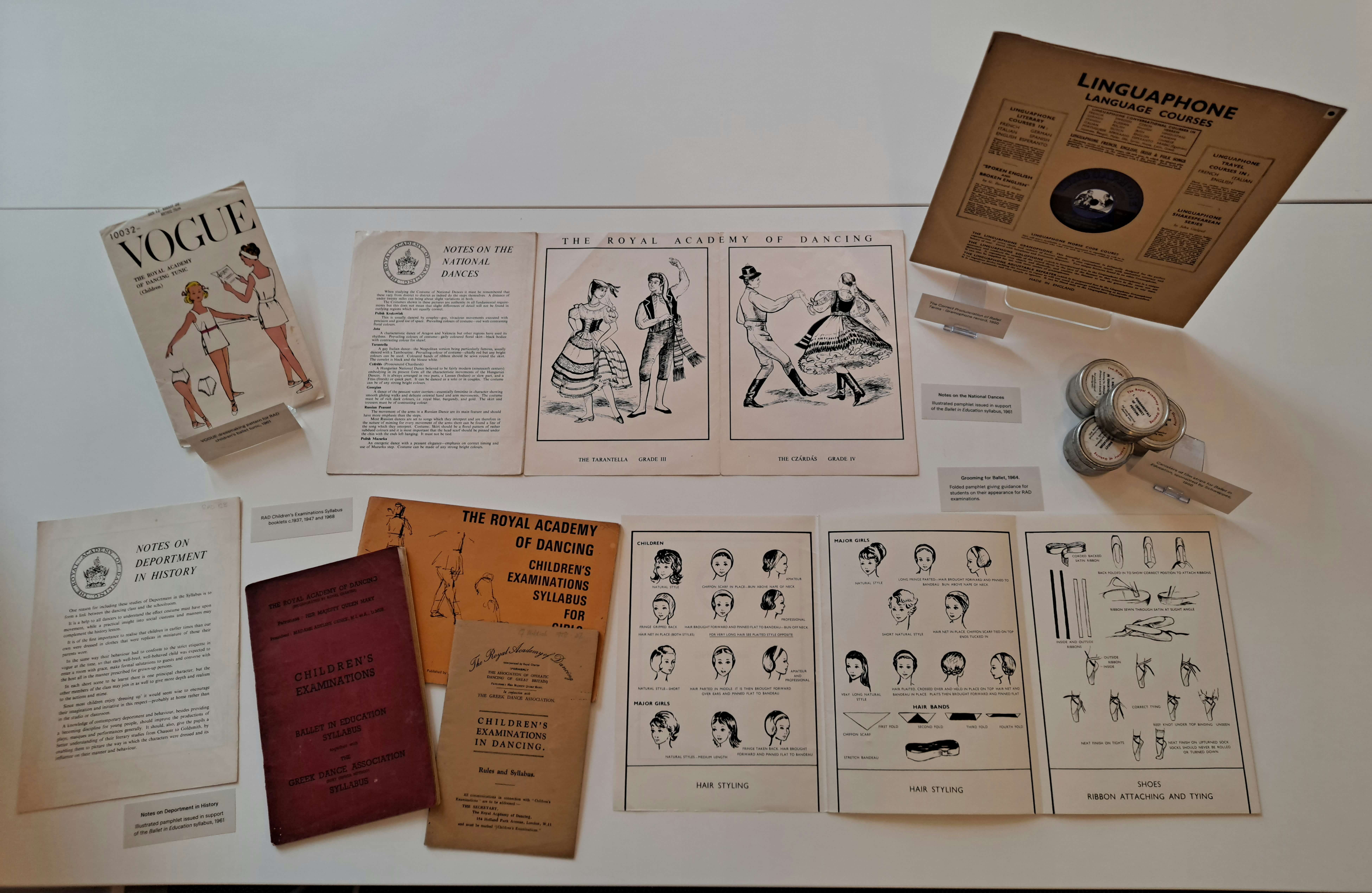

The archive holds information on our heritage and the development and history of British ballet. This includes rare books, theatre programmes, photographs, costume designs, scrapbooks, pictures and artefacts, as well as audio-visual materials and paper-based documents and correspondence.

Opening times

We look forward to seeing you.

Please make an appointment to visit us so that we can ensure resources and staff are available for you.

Access to archive materials is available Mon-Thu 10:00 – 17:30 only and strictly by appointment.

- Opening hours

- Changes to opening hours

Monday

9:30am – 6pm

Tuesday

9:30am – 6pm

Wednesday

9:30am – 6pm

Thursday

9:30am – 6:30pm

Friday

9:30am – 5pm

Please phone The Wolfson Library at +44 (0)20 7870 8873, or email library@rad.org.uk to confirm opening hours.

The library catalogue

The online library catalogue contains details of all materials in our collections

You can use the online library catalogue to find out what we have in stock and what is currently available or out on loan. You can also use it to check references or bibliographic details. Searches may be general (use the simple search form) or specific (use the advanced option) and if you are registered on a Faculty of Education programme you can also search by reading list (other searches/lists). Results can be modified and refined. Search results can also be exported, saved or printed for future reference and are available in summary and detailed form.

The online library catalogue webpage includes ‘search tips’ so you can make the most of our catalogue. Our ‘featured resources’ section highlights books and other library material included in our temporary exhibition library displays. The ‘new items’ section allows you to browse the latest library arrivals. You will also find instructions to download the Liberty Link Mobile App so you can search, reserve and renew library resources using a mobile device.

Archives & Special Collections

The archive of the RAD is comprised of several collections, the RAD Heritage Archive includes past copies of exam syllabi, minutes of committee meetings, prospectuses, course brochures and annual reports, documents, papers and photographs relating to events and activities throughout the organisation’s over 100-year history.

These are housed alongside the personal collections of notable figures in the history of British ballet. An archive catalogue and database that will allow all collections to be searched is under development and will be available online in the future.

History of the Wolfson Library

Take a virtual tour of On Point: Royal Academy of Dance at 100 an exhibition which ran from 2 December 2020 to 29 August 2022 at the V&A Museum in London. The RAD’s story, from its foundation to its influence on ballet and dance internationally, was told through objects from the RAD’s archive and the V&A’s Theatre & Performance Collection.

RAD Book Club

RAD Book Club is open to RAD staff, FoE students, and local residents and has been regularly meeting, every 4-6 weeks since 2015 to discuss books suggested by its members.

See what we have been reading here.

Interested in joining? Contact us for more information

Frequently asked questions

Can I visit the Library and Archive?

The Library and Archive is free to visit for RAD members, Benesh Members, RAD students and staff. If you are interested in consulting specific material, please drop us an email with the details.

For other visitors, there is a fee to access the Library and Archive and its resources. Please contact us with the details of your research and make an appointment.

How do I borrow books?

All Royal Academy of Dance permanent members of staff and UK-based students enrolled on one of the Faculty of Education programmes are entitled to borrow Library material from the Library’s circulating stock.

RAD Members and Benesh Members can also become Library Subscribers, which allows up to four items to be borrowed from the circulating stock (with some restrictions).

To find out about becoming a Royal Academy of Dance Member, click here. To become a Benesh International member, click here. Confirmation of membership may take a week to arrive.

For a Library Subscription Application Form, please contact us. You will need your Royal Academy of Dance or Benesh Membership number when applying.

Can I donate material to the Library and Archives?

Donations

The Wolfson Library at the Royal Academy of Dance is pleased to accept donations of dance-related material that complements or enhances existing collections. The Library reserves the right to dispose of any material that is no longer needed or falls outside the scope of our existing collections. Donations may not be accepted if you wish to place any restrictions on their use or disposal.

Books, Journals, CDs and DVDs

Please email the library with a list of the items that you are offering before you send us any items. You can search our catalogue first to reduce the chances of offering items which we already hold. Any items sent to us without our prior agreement and which are not suitable to add to stock will usually be sold with the income used to support the Royal Academy of Dance and the work of organizations such as the Literacy Trust and RNIB.

Archival material

Please read the RAD Archive Collections Development Policy.

If you wish to donate to the archives, please contact the Archives and Record Manager to discuss the suitability of the material you wish to donate.

What are your opening hours?

The Library and Archive of the Royal Academy of Dance is open to members, students, staff and visitors during these times:

- Monday 9:30am – 6pm

- Tuesday 9:30am – 6pm

- Wednesday 9:30am – 6pm

- Thursday 9:30am – 6:30pm

- Friday 9:30am – 5pm

If you are a visitor, please contact us to make an appointment.

How can I see what’s in your collections?

The online Library catalogue contains details of the library’s general reference collections, including books, journals, articles, CDs, DVDs, Benesh Movement Notations scores and resource packs.

The Archive of the Royal Academy of Dance includes past copies of exam syllabi, minutes of committee meetings, prospectuses, course brochures and annual reports alongside various documents, papers and photographs. Our special collections include rare books, manuscripts and transcripts, notebooks and scrapbooks, music scores, programmes and souvenir brochures, photographs, costume designs, and artefacts and artworks.

Contact information

For enquiries, please email library@rad.org.uk or call +44 (0)20 7870 8873.

You can write to us at:

Library and Archive, Royal Academy of Dance, 188 York Road, Battersea, London, SW11 3JZ, United Kingdom

Library Staff

All library staff are happy to help with any enquiry but their particular areas of responsibility are as follows:

Subscribe to our mailing list

- Be the first to hear about our news and events

- Choose the type of news that interests you

- Get discounts from the RAD shop