Our People

Our dedicated and loyal worldwide staff rely upon the efforts of our executive board, the guidance of our board of trustees, and the passion of our president and vice presidents to fulfil our mission.

President & Vice Presidents

-

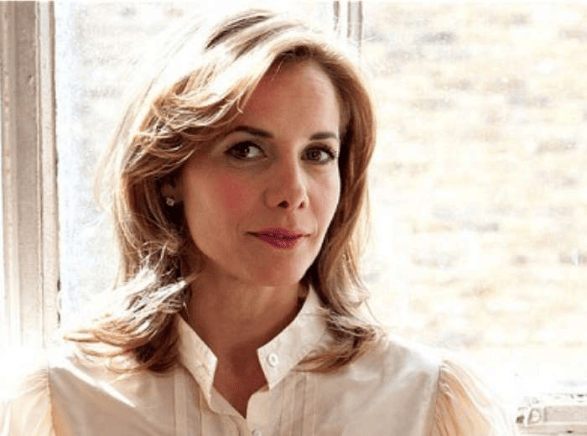

Dame Darcey Bussell DBE

President

Darcey Bussell is a former Principal with The Royal Ballet and the most famous British ballerina of her generation. During…

-

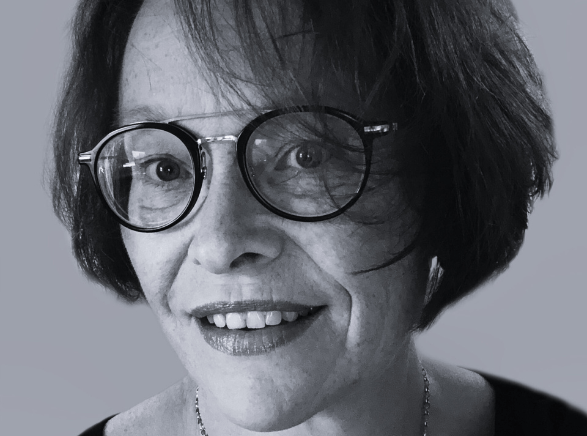

Dame Monica Mason DBE

Vice President

Born in Johannesburg, Monica Mason came to England at the age of 14 and trained with both Nesta Brooking and…

-

David McAllister AC

Vice President

A graduate of The Australian Ballet School, Perth-born David McAllister joined The Australian Ballet in 1983. David was promoted to…

-

Li Cunxin AO

Vice President

Li Cunxin began dancing at age 11 when he was selected to join Madame Mao’s Beijing Dance Academy. Graduating in…

-

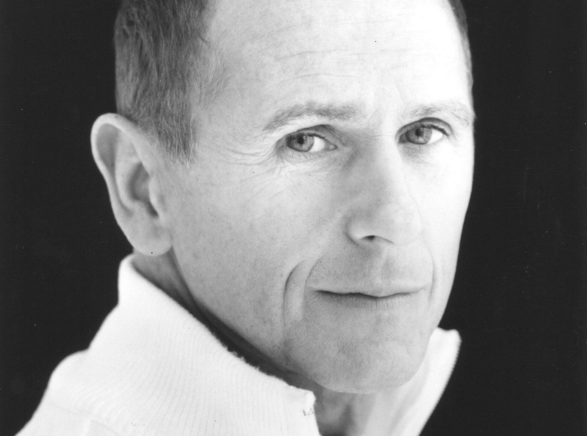

Sir David Bintley CBE

Vice President

Born in Huddersfield, Sir David Bintley trained at The Royal Ballet School and joined Saddler’s Wells Royal Ballet in 1976.…

-

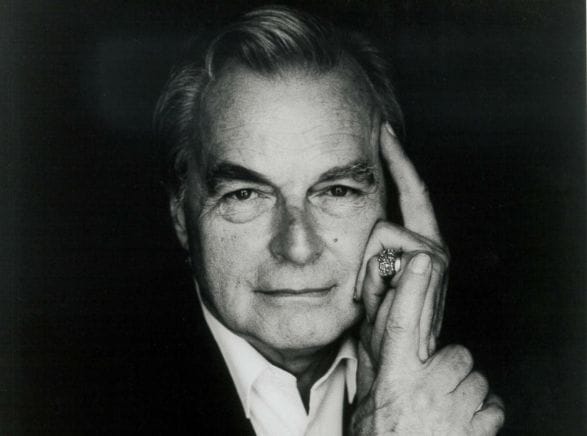

Sir Peter Wright CBE

Vice President

DMus DLitt FBSM Peter Wright made his debut as a professional dancer with the Ballets Jooss during World War II,…

-

Wayne Sleep OBE

Vice President

Wayne Sleep won a scholarship to The Royal Ballet School at the age of twelve and later became a Senior…

The Board of Trustees

-

Amy Giancarlo

Dance Teacher, The Royal Ballet School, Rambert and The Ballet School London

BA (Hons) RBS DDT LRAD ARAD RAD RTS Amy Giancarlo has been an active RAD teaching member since 2011 and…

-

Catherine Quinn

Chair of Governance and People Subcommittee

BA (Hons) MA, MBA Catherine Quinn’s career over the last twenty years has crossed sectors, from research, science and innovation;…

-

Deborah Cornelius

Board of Trustees

MA (Cantab) Initially qualifying as a Corporate Lawyer at Freshfields, Deborah Cornelius spent four years as a strategy consultant at…

-

Esther Chesterman

Chair of Examinations and Regulatory Subcommittee

LLM LLB Dip Ed Esther Chesterman worked in education for over 25 years. After completing a master’s degree in law,…

-

Georgina Robbins

The Board of Trustees

Georgina Robbins has been a proactive and committed supporter of RAD governance, fundraising, and values over the last five years.…

-

Imogen Knight

Chair of Artistic and Deputy Chair of Global Membership & Marketing Subcommittees

ARAD, BA (Hons), DDE, RAD TD, RAD RTS Imogen is passionately committed to dance teachers everywhere having access to great…

-

James Cane

Chair of Finance and Audit Subcommittee

FCA James has served as a trustee, and as chair of the Finance, audit and risk subcommittee since 2021. He…

-

Justine Berry

Board of Trustees

PDTD ARAD RTS PGCert. MA Justine Berry has enjoyed 20 years as a dancer and deeply appreciates having found another…

-

Peter Flew

Chair of Education Subcommittee

Peter is currently Director of the School of Education at the University of Roehampton in South West London, one of…

-

Rachel Jackson-Weingärtner

Board of Trustees

MA, RAD RTS., SAC Dip (Child Psychology), LISTD Dipl Living in Germany since 1992, Rachel has been involved with the…

-

Stephen Moss CBE

Chair of the Board of Trustees

Stephen trained as a lawyer and holds an MBA from London Business School. After a spell in the City of…

-

Steve Sacks

President, Advisory Board for the Arts (Europe)

Steve brings a combination of a passion for ballet and for education; expertise in strategy, marketing and digital; and extensive…

-

Vikki Allport

Board of Trustees

RAD RTS T.DIP (Dist) Vikki’s first and foremost passion is dance, and she is extremely proud to belong to the…

The Executive Board

-

Alexander Campbell

Artistic Director

Alexander trained at The Royal Ballet School and joined Birmingham Royal Ballet on graduation. He joined The Royal Ballet as…

-

Elizabeth Honer CB

Chief Executive

Elizabeth has had a lifelong love of dance, starting her career at Sadler’s Wells and most recently through classes at RAD…

-

Mary Keene

Director of Examinations

Mary has worked in education for nearly 20 years now, primarily in the Arts but also in Engineering and Medicine.…

-

Max Goldman

Director of Fundraising and Development

Max is a fundraiser with over a decade of experience in various UK charities. Before joining the Royal Academy of…

-

Penny Cotton

Membership Director

Penny comes to her role as Membership Director after nearly 14 years of managing membership schemes for several large organisations.…

-

Renu Randhawa

Director of Finance

FCA Renu started her career at PwC, qualifying as a Chartered Accountant before joining Plan International where she was responsible…